- Home

- Russell Edson

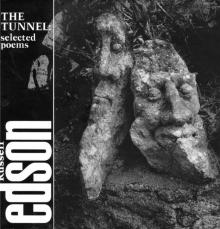

The Tunnel

The Tunnel Read online

THE TUNNEL:

selected poems

Copyright © 1994 by Russell Edson. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address Oberlin College Press, Rice Hall, Oberlin College, Oberlin, OH 44074.

The poems in this volume previously appeared in the following collections: The Very Thing That Happens © 1964; What a Man Can See © 1969; The Clam Theater © 1973; The Childhood of an Equestrian © 1973; The Intuitive Journey © 1976; The Reason Why the Closet-Man Is Never Sad © 1977; The Wounded Breakfast © 1985.

Publication of this book was made possible by a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Edson, Russell, 1935-

The Tunnel: Selected Poems / Russell Edson.

(FIELD Poetry Series; 3)

I. Title

L.C. 93-087296 ISBN 0-932440-66-5

0-932440-65-7 (pbk.)

* * *

For FRANCES

I

from The Very Thing That Happens

Clouds

A husband and wife climbed to the roof of their house, and each at the extremes of the ridge stood facing the other the while that the clouds took to form and reform.

The husband said, shall we do backward dives, and into windows floating come kissing in a central room?

I am standing on the bottom of an overturned boat, said the wife.

The husband said, shall I somersault along the ridge of the roof and up your legs and through your dress out of the neck of your dress to kiss you?

I am a roof statue on a temple in an archaeologist’s dream, said the wife.

The husband said, let us go down now and do what it is to make another come into the world.

Look, said the wife, the eternal clouds.

A Chair

A chair has waited such a long time to be with its person. Through shadow and fly buzz and the floating dust it has waited such a long time to be with its person.

What it remembers of the forest it forgets, and dreams of a room where it waits — Of the cup and the ceiling — Of the Animate One.

How a Cow Comes to Live with Long Eared Ones

A rabbit had killed a man in a wood one day. A cow watched waiting for the man to stand up. An insect crawled on the man’s face. A cow watched waiting for the man to stand up. A cow jumped a fence to see closer how a rabbit does to a man. A rabbit attacks a cow thinking the cow may come to aid the man. The rabbit overcomes the cow and drags the cow down into its hole.

When the cow comes awake the cow thinks, I wish I was on top of the earth going with the man to my barn.

But the cow must remain with these long eared ones for the rest of its life.

Father Father, What Have You Done?

A man straddling the apex of his roof cries, giddyup. The house rears up on its back porch and all its bricks fall apart and the house crashes to the ground.

His wife cries from the rubble, father father, what have you done?

Of the Snake and the Horse

The snake is a thin beast, longer much than wide. Its head is a poisonous jewel. It comes to remind humankind that fear has form and evil shape, said father.

I like the horse so much better, father, said mother.

The horse has a human arse and a cow’s head, said father.

And the horse tramples the snake, doesn’t it, father, because the horse is on the side of humankind, isn’t it, father? said mother.

The horse was invented by man after the horseless carriage; since the carriage was horseless they said let us invent a horse. At first the horseless carriages were afraid of the horses, mechanical things are terribly timid. But behind the invention lay the weapon that does the thin beast, longer much than wide, under its hooves, said father.

Was that how man was saved again to dwell in paradise, father? said mother, and why this is the best of all possible worlds?

This is the best of all possible worlds only because it is the only one that showed up, said father.

Shall we wait for the others? said mother.

Shall we wait for the others? … You stupid thing, said father.

A Machine

A man had built a machine.

… Which does what? said his father.

Which gets red with rust if it rains, wouldn’t you say so, father?

But the machine is something to put a man out of work, said his father, and as work is prayer, so the machine is a damnation.

But the machine can also be sweethearts, growing cobwebs between its wheels where little black hands crawl; and soon the grasses come up between its gears — And its spokes laced with butterflies …

I do not like the machine, even if it is friendly, because it may yet decide to love my wife and take my bus to work, said the father.

No no, father, it is a flying machine.

Well, suppose the machine builds a nest on the roof and has baby machines? said the father.

Father, if you would only stare at the machine for a few hours you would learn to love it, to perhaps devote your very life to it.

I would not do no such a thing, not with your mother watching, itemizing my betrayals with which to confront me in bed … Perhaps I would soften toward this humble iron work, for even now I feel moved to assure it that there is a God, yes, even for you, dear patient machine. But your mother is watching. Even my mother is watching. All the women of the household are watching from the windows, waiting to see what I shall do.

But father, look at the dew on its wheels, does it not make you think of tears?

Would you break my heart whilst the women watch, half hoping that I shall weaken? for they are hungry for the victim that would be a kindness for me to deliver.

Then bow to the machine, father, be kind to the women as you are kind to the machine.

Oh no, dear child, I could not bow to a machine; I am, after all, human. Let others open new doors of history …

Waiting for the Signal Man

A woman said to her mother, where is my daughter?

Her mother said, up you and through me and out of grandmother; coming all the way down through all women like a railway train, trailing her brunette hair, which streams back grey into white; waiting for the signal man to raise his light so she can come through.

What she waiting for? said the woman.

For the signal man to raise his light, so she can see to come through.

The Fetcher of Wood

An old man got into a soup pot and shook a wooden spoon at the sky.

When he had finished he went upstairs to his room and died.

When his wife came home she said, stop being dead, there is no reason for it.

He got out of bed. So you’re dead, what of it? she said. I have no patience with you today — Go fetch wood for the stove.

He collapsed onto the floor. Oh, go along with you, you can at least fetch some wood. She kicked the corpse to the stairs and over the edge, and it fell to the first floor. Now, fetch wood, she screamed.

The corpse dragged itself out of the door. Spiteful old man, she said to herself, died just to get out of fetching wood.

The old man’s cadaver was trying to chop wood. The ax kept slipping out of its hands. The cadaver had cut off one of its legs below the knee.

Now the cadaver came hopping on one leg into the kitchen, carrying its leg. Oh, you’ve cut my old man’s leg off, she screamed. And she was so angry that she fetched the ax and began to chop up the corpse — Chop your leg off to get out of work, will you? — Die when I need you to bring the wood in,

will you? …

The old man, leaning over a cloud, watched the old woman chopping up his corpse — Give it hell, baby, give it one for me …

When the old woman had finished, she gathered up the pieces and put them into a soup pot — Now die to your heart’s content — And tell me you can’t fetch wood …

Dinner Time

An old man sitting at table was waiting for his wife to serve dinner. He heard her beating a pot that had burned her. He hated the sound of a pot when it was beaten, for it advertised its pain in such a way that made him wish to inflict more of same. And he began to punch at his own face, and his knuckles were red. How he hated red knuckles, that blaring color, more self-important than the wound.

He heard his wife drop the entire dinner on the kitchen floor with a curse. For as she was carrying it in it had burned her thumb. He heard the forks and spoons, the cups and platters all cry at once as they landed on the kitchen floor. How he hated a dinner that, once prepared, begins to burn one to death, and as if that weren’t enough, screeches and roars as it lands on the floor, where it belongs anyway.

He punched himself again and fell on the floor.

When he came awake again he was quite angry, and so he punched himself again and felt dizzy Dizziness made him angry, and so he began to hit his head against the wall, saying, now get real dizzy if you want to get dizzy. He slumped to the floor.

Oh, the legs won’t work, eh? … He began to punch his legs. He had taught his head a lesson and now he would teach his legs a lesson.

Meanwhile he heard his wife smashing the remaining dinnerware and the dinnerware roaring and shrieking.

He saw himself in the mirror on the wall. Oh, mock me, will you. And so he smashed the mirror with a chair, which broke. Oh, don’t want to be a chair no more; too good to be sat on, eh? He began to beat the pieces of the chair.

He heard his wife beating the stove with an ax. He called, when’re we going to eat? as he stuffed a candle into his mouth.

When I’m good and ready, she screamed.

Want me to punch your bun? he screamed.

Come near me and I’ll kick an eye out of your head.

I’ll cut your ears off.

I’ll give you a slap right in the face.

I’ll break you in half.

The old man finally ate one of his hands. The old woman said, damn fool, whyn’t you cook it first? you go on like a beast — You know I have to subdue the kitchen every night, otherwise it’ll cook me and serve me to the mice on my best china. And you know what small eaters they are; next would come the flies, and how I hate flies in my kitchen.

The old man swallowed a spoon. Okay, said the old woman, now we’re short one spoon.

The old man, growing angry, swallowed himself.

Okay, said the woman, now you’ve done it.

A Red Mustache

A heavy woman with a rolling pin said, I am the king.

A fly lighted on her nose. She hit the fly on her nose with her rolling pin. Do not disturb her highness with trivialities, she said, as the blood from her nose formed a red mustache.

Darling, said her husband, you have a red mustache.

The woman who is king backed up.

Her husband watched her red mustache.

The woman who is king came forward.

Her husband watched her red mustache and said, darling, what’s with the red mustache?

I am king of everything, she said, I am king Mama.

And the rolling pin, dearest? he said.

Is the scepter of brutality, she said.

And the apron and the hair in its greasy little bun? he said.

Which is the fortress and the image that people shall come to fear, she said.

And the red mustache, so outlandish on a fat middle-aged hausfrau? he said.

The red mustache which you constantly refer to is the sign of office, the change of gender, the self inflicted blow, the secondary hair of my manhood, the end of my menopause, the return to maidenhood, the cerebral menses from my nose instead of my under part … , she said.

But what about the red mustache? he said.

If you really must know I killed a fly on my nose with a rolling pin, she said.

No you didn’t, he’s flying around on the ceiling, he said.

Oh look, he’s on your head, she said.

Hold it, he screamed.

I must kill it, she said.

No, don’t, he screamed.

It’ll get on my nose, she said.

Oh please clean the blood off your face and cook dinner, he screamed.

Oh oh oh, she cried, I do not know what to do. Oh oh oh …

Wash your face, he said.

No, that is not a thing to do, oh oh oh, she cried.

Well what is it, suddenly, with that red mustache? he said.

Oh I want to be loved more than all things else, oh oh oh … , she cried.

Appearance

There was a landscape once in a while where a rock a person and a pebble and will it rain one day, gathered one day to appear.

There was a landscape that became a room to search for a house, to decide to stay there, then to be old in a house it finds.

And so the sun came in a room’s window and woke a person who poured coffee out of a cup into his head.

A Man Who Writes

A man had written head on his forehead, and hand on each hand, and foot on each foot.

His father said, stop stop stop, because the redundancy is like having two sons, which is two sons too many, as in the first instance which is one son too many.

The man said, may I write father on father?

Yes, said father, because one father is tired of bearing it all alone.

Mother said, I’m leaving if all these people come to dinner.

But the man wrote dinner all over the dinner.

When dinner was over father said to his son, will you write belch on my belch?

The man said, I will write God bless everyone on God.

Love

Dog, love me, said a man to a dog. A dog said nothing.

But a piece of glass when properly with the sun glittered into his eye

— I hear you, said the man.

But a leaf wristing on its stem because the wind wanted to go someplace, turned the man to itself — So you are saying such and such, he said.

He noticed wrinkles on his shoe — Muscle stretch which is what a smile is; my shoe is smiling at me. Shoe, I love you, love me. But his shoe merely walked on, his head hovering above it …

Head, head, love me, he said to his head.

His head had a nostril. He felt it. There were two. One nostril must have had a baby.

But his nostril blew air at his fingers.

I can blow air at a nostril too. So he screwed up his lips and blew air at his nostrils.

The Definition

He that puts suicide into his left ear pretends it is wax. His mother says, but it’s a bullet which you have shot yourself with.

Is that how I died? he said.

That’s when the funeral began, it was like a flower festival; your father asked me to marry him, and with much declining as to appear of greater value I agreed. Of the two of us, your father and I, so overlapping we blurred into three. I said, how is this? Your father said, this is this. And this was you. But for a time we could not tell who any of us were. Your father said, who am I? And I said, am I you? And he said, if you are me then I am the small one there and the small one is you. And after much declining I agreed to be anyone; I said, someone is passing the house, shall I be someone passing the house? … and so forth. Until we discovered that we had shadows; so that in the morning we would assemble and let the sun stencil us on the wall: The largest of the three we allowed would be the father, the next largest, the mother, and the smallest, the third one, which you were called as we did not know who you were …

And that you might be a wood god or the spirit of the house … So that we allowed

you to define yourself.

But of my suicide? …

But you see that is another definition of the first turning which was turned when I wasn’t looking …

And of my death? …

As a festival of flowers … declining as to appear of greater value …

A Stone Is Nobody’s

A man ambushed a stone. Caught it. Made it a prisoner. Put it in a dark room and stood guard over it for the rest of his life.

His mother asked why.

He said, because it’s held captive, because it is the captured.

Look, the stone is asleep, she said, it does not know whether it’s in a garden or not. Eternity and the stone are mother and daughter; it is you who are getting old. The stone is only sleeping.

But I caught it, mother, it is mine by conquest, he said.

A stone is nobody’s, not even its own. It is you who are conquered; you are minding the prisoner, which is yourself, because you are afraid to go out, she said.

Yes yes, I am afraid, because you have never loved me, he said.

Which is true, because you have always been to me as the stone is to you, she said.

Fire Is Not a Nice Guest

I had charge of an insane asylum, as I was insane.

A fire came, which got hungry; so I said, you may eat a log, but do not go upstairs and eat a dementia praecox.

I said, insane people, go into the attic while a fire eats a kitchen chair for breakfast.

But fire wanted a kitchen curtain, which it ate and climbed at the same time, and went then into the ceiling to eat a rafter.

The Tunnel

The Tunnel